- Home

- H. Laurence Lareau

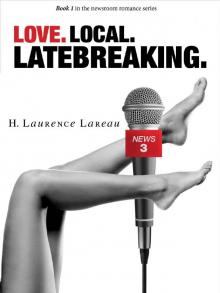

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series Read online

Love. Local. Late-Breaking.

by

H. Laurence Lareau

Copyright © 2016 H. Laurence Lareau

All rights reserved

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your favorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Prologue

Palm Beach, Florida

May 6

Station Manager’s office

Karli listened as the news director and general manager’s leaden rejection made her stomach sink. The four years of extra hours, extra shifts, extra stories, and extra effort had all apparently come to nothing. She stared in shocked, frozen disbelief as she realized that the high quality and huge volume of her work as a television journalist meant nothing.

“How could you give the main anchor spot to her?”

“She has the gravitas we need, the overall look we need, the delivery we need to increase trust with the viewers and increase our ratings, Karli,” the general manager said.

The news director was quick to add, “And Karli, you just don’t have the kind of seniority to carry the weight of the station.”

“You led me on the whole time I’ve been here, didn’t you? Just so you could get more out of me.” Karli was surprised at how calmly she expressed her fury at their betrayal.

“Led you on? What are you talking about? We never did that.” The two heads glanced at one another, shaking their mutually reinforcing denials.

“No?” Karli responded. “Do this series on your own time and you’ll be destined for big things here, Karli. Or how about We need you to cover Thanksgiving, but don’t worry, you’re next in line for a big reward. Haven’t I done every crazy thing you’ve asked for the last four years?”

“Of course you have worked hard,” the news director was taken aback. “The whole news team works hard. It’s an expectation of this station—of this business—that reporters work hard. It takes years of hard work to develop the depth and maturity to carry a lead anchor’s role.”

“So I’ve worked hard, I’ve developed sources and relationships, I’ve paraded the station’s colors through the community, and now you tell me I’m shallow and immature?”

The news director heaved a belabored sigh, repeating a mannerism that Karli had always disliked. In this tense moment, dislike became loathing. She opened her mouth to protest, but the news director’s raised finger triggered the restraint of four years’ regarding this man as her boss. She paused while he spoke.

“Just because you don’t have what it takes to be the main anchor right now does not mean that you aren’t a solid newswoman. You have a unique ability to interview anyone from Joe six-pack to the governor with great effectiveness. You have a strong on-camera presence and a good voice. But you’re not seasoned enough to be taken as seriously as a main anchor must be.”

He shrugged, reacting to the rebellion on her face. “And we expect you to improve dramatically behind the camera, too. You usually catch most of the video necessary to file a solid story, but there’s no question that you come up short on both the technical and artistic side of television news.

You don’t think about audio until you’re editing, if ever. You need more time in the trenches before you can expect to move up.”

“Thank you for your feedback,” Karli said, more by way of using her good manners to end the conversation than from actually wanting to express gratitude. She turned and left the business office and walked toward the building’s other wing, which housed the newsroom.

She stormed down the hallway, vision blurred by tears of frustration. She half wanted and half feared meeting a fellow journalist who could see her tears and commiserate with her mistreatment. She was relieved, however, to get to an edit suite where she could slam the door and sob in sound-insulated silence.

Karli had a generous portion of the ego required for her chosen profession, and had believed—still believed—that success was only a matter of time. She had approached the interview and the morning’s meeting full of confidence that she had earned her way to the anchor desk.

As she replayed the comments in her memory, they boiled down to thanking her for doing lots of extra work for free, expecting that she would do even more work for free, and somehow thinking that would ‘season’ her enough to make her anchor material.

And of course their ignorance extended to expecting her to become a better photog, too—which was nonsense, since she wouldn’t have to shoot her own stories once she left podunk Palm Beach for a market big enough to be worth going to. Stations in moderate to major markets all employed professional news photographers, and journalists there looked down their noses on small markets where reporters worked as one-man-bands.

The anchor job wasn’t really the object of her ambition, either, Karli reflected. She had applied for the job because it came open when the previous anchor had moved on to Nashville. Because she did not believe in half-measures, she had committed herself fully to landing the job.

Now that the opportunity had evaporated, that email from the news director in Des Moines, Iowa flitted across her mind. She pulled out her iPhone and re-read the email she had so lightly skimmed last night, when she had been sure of staying in Palm Beach as the main anchor.

“Karli,” the email read, “Thanks for sending the link to your reel on YouTube. You’re doing a lot of things we like to see here at Three NewsFirst. Please give me a call to talk about opportunities here. Regards, Jerry Schultz, New Director.”

Des Moines has a reputation for really great news photographers, Karli reflected. Collaborating with them could help me to do really great reporting, the kind that can propel me on to even bigger markets where I can really have an impact. It’s the center of a thousand-mile cornfield, but at least it’s only a six-hour drive to Chicago. Good reporting should be able to reach a major market that’s that close, even wading through corn.

The number was below his name. Karli tapped the link to dial it.

Chapter One

Just east of Cambridge, Iowa

Tuesday, July 16

Live shot for noon newscast

“It isn’t safe here,” Karli Lewis said. “We need to get the gear back in the truck and move.” Iowa’s humid west wind ruffled Karli’s long, glossy black hair as she looked from the hazard sign on the train’s side to her iPhone’s screen. The midwestern haze caught light from the noon-vertical sun and scattered it in every direction, making shadows faint and blurred. Reflected heat radiated from the weeds and stubbled grass along the railroad tracks.

She waited tensely as news photographer Jake Gibson ignored her, carefully framing the cracked and leaking drums thrown from the railroad car in his camera’s viewfinder. Karli checked her iPhone again and sniffed the increasingly acrid air, a growing sense of danger making her impatient. She took in a breath, preparing to telling Jake yet again that it wasn’t safe to stay. Jake, still looking only into his viewfinder, pressed the record button and held up his index finger to quiet her while the video rolled. Years of news-gathering habit make Karli’s silence automatic; the natural sound recorded through the photographer’s microphone is often just as important as the video.

Everything he was doing got on her nerves. He was obviously competent, Karli obs

erved as she watched Jake’s strong, tanned forearms reach to carefully touch on the camera’s controls. In spite of her impatience, she was impressed with the steady, masculine care he used with his equipment.

He was obviously in fantastic shape, too. He moved and carried dozens of pounds of video equipment effortlessly and very precisely. And when he was in the actual act of shooting, like now, his strength was coiled and motionless, almost as though he were cast in sculptural bronze. Karli resisted the temptation to ruin the shot and make that Greek sculpture of a man move. She watched a drop of sweat map its path down from his unmoving temple and along the stern line of his jaw.

Further irritating Karli, Jake concentrated only on his shot, oblivious to the sweat and her impatience. After an interminable five seconds, Jake stopped the recording, raised his eye from the viewfinder, and returned her impatient look with a questioning quirk of his eyebrow.

“Let’s go,” she said, dark blue eyes flashing from her tanned face. “Now.”

“This is the perfect spot to go live from,” Jake responded firmly, locking his camera in place atop its tripod. “We’re close enough that the railroad cars will be right there in the shot,” he began, ticking the points off on his fingers. “The live truck has a signal locked into the station. We only have about ten minutes till the newscast starts. And we even have enough cable that you could do a walking live shot right up to the derailed train cars.”

Karli could see by the dark eyebrows drawn together under Jake’s light brown curls that he also was impatient—and he wasn’t packing up his equipment.

She bent over, unplugged the cables leading to her earpiece and microphone, and strode, her tanned and athletically toned legs stretching swiftly right past Jake to his camera and tripod. She snatched them up decisively and headed for the live truck. “Pull the mast down right now, Erik!” she shouted. “We have to move to the west before the newscast starts.”

Startled by her commanding tone, the engineer in the live truck started throwing switches and talking into his two-way radio. To the thrum of its electric motor, the long pole supporting the truck’s microwave transmitter telescoped back into itself and the truck.

“Just who do you think you are?” Jake’s furious question startled Karli. She hadn’t heard his footsteps catching up. “We have an actual newscast to put on the air, and tens of thousands of loyal Three NewsFirst viewers are going to be watching a big fat nothing because you don’t feel safe? I don’t know what you did in the lazy tropics, but we’re journalists here, and that means we don’t just phone the news in—we actually cover it where it’s happening.”

“You can’t talk to me like that,” snapped Karli, who had turned away from Jake when he finally stopped talking. She turned back to face him just as she’d been about to dump the camera and tripod inside the van. “Good reporting is the same everywhere, and I spent four years doing good reporting in Palm Beach before I came here to the absolute center of flyover country.”

“Uh, kids,” Erik asked, sticking his head out of the van’s large side door, “are we going to move or do you need to get a couples therapist? Because the mast is almost down and master control is asking when we plan on locking in a new signal.”

Karli questioned, not for the first time, her decision to move to the center of Iowa for this job. She had chosen her career in broadcast news deliberately and against her father’s wishes.

Her father had wanted—he still wanted—to put her on the fast track to prosperity and security. And he nearly always got what he wanted. He was a powerful and politically connected attorney in Charleston, SC. And he came from a long line of powerful Lewises. He was carrying on the tradition of marrying money, making more of it, and making sure that each succeeding generation fulfilled its role in Charleston’s political and social elite.

Rebellion for Karli had taken the form of excelling in her chosen field. And journalism had definitely been a field she had chosen, not her father. Instead of plunking her in places she couldn’t possibly have anticipated, where each person she met would have a new story for her to tell—including the lonely cornfields of Iowa—her father’s plan would have put her near the center of a busy and deeply connected social network where she knew everyone and everyone knew her. And the plush public relations career he had planned for her dovetailed with his anticipated run for Attorney General.

But his plan was not hers. Karli loved meeting new people, learning their stories, and telling them in her reports—even considering the meager wages. But right now, in this heat, and with this photographer arguing with her, a little money and an air-conditioned office sounded pretty good. At least, she considered, she wouldn’t have to schlep heavy video gear through tangled weeds in her Calvin Klein black heels.

She called her real ambition to mind, though: to do great reporting in a major market, where the issues had broad and deep effect, where good reporting was needed to unmask corruption and work to make power more honest and responsive to the people. Karli had fought hard to earn her reputation as a relentless and meticulously accurate reporter. She had also earned a reputation—one she was less conscious of—as a deeply compassionate interviewer, one who could quickly relate to people from all walks of life. Her curiosity about each person she met was intense and sincere. The attention she gave to the people she interviewed was complete and marked by the kindness and compassion that makes people feel like they’re the only other person in the world. That disarming ability to reach people’s hearts filled her interviews with revelations that flowed smoothly from the trusting intimacy people found with her immediately and almost universally.

What her stories in Palm Beach had lacked—and what she had come to Iowa for—was photography that could achieve that same kind of intimacy and complement the reporting she was learning to do so well. Working here in the cornfield brought her to a market where the news photographers excelled—especially Jake, if the gossip she’d gathered proved correct. And if she could report some stories that showed her working at her peak, supported by excellent news photography, that would catch hiring eyes in the big markets she was headed for.

“Hey! Easy on my camera!” a loud voice interrupted her thoughts. Looking back over her shoulder, Karli saw Jake’s long, muscular arms reaching futilely for his equipment. Behind him, the whirling lights of fire trucks raced toward them.

She had already spent enough years in the news business to understand the stereotypical news photographer personality. “Look, Jake, lay off,” she said. “Everyone knows that photogs only care so much for those long telephoto lenses because they’re compensating for something. And we really need to get moving.”

A dangerous light flickered behind Jake’s limpid brown eyes. His 6’ 3” frame froze, taut with tense emotion. He had been in the news business even longer than she, and he knew his stereotypes, too.

He replied, “If we’re going to talk about what everyone knows, maybe we should touch on little reporter bunnies. Everyone knows that baby girl TV reporters come in two flavors: the most common are the attention whores who have enough intellectual capacity to know exhibitionism is healthier when it masquerades as reporting. But they still put on a great show—on the air and in the bedroom.”

His gaze bore into her as he continued. “You’re probably the second type, though: the repressed prude who can’t abide the thought of actual sex with a man, so you take your daddy issues with you in front of the camera. The attention of a news shooter and the viewers he stands in for are a poor substitute for the sex you’re too frigid to actually have. And you think dry-humping your long-suffering, long-distance boyfriend is daring and maybe too racy for you. So you’re frustrated and driven and angry and bitchy. And the only thing that you think will help is a bigger audience. But it doesn’t matter how big the audience—or how long the lens—they can’t relieve your frustration.”

Karli actually heard herself shriek at this impertinence, and as she saw the handsome, devilish grin tugging at the c

orners of his mouth in response, she shrieked again.

Then she took a deep breath preparatory to shouting him off his high horse.

Erik the engineer had been listening as he readied the live truck’s many delicate machines and instruments to move. He poked his head out again just in time for Karli’s second shriek. “Hey guys, your stereotypical engineer can’t promise anyone that he’ll be able to get a signal out of the new location if we don’t get there soon. I can’t necessarily work a miracle every time, no matter how great my press has been.”

“Save it, Karli,” Jake said calmly, a grin now dimpling his cheek and chin. “The point is that maybe we are both actual people instead of the reductive stereotypes you have so handy.” He reached across her to retrieve his camera, gently but irresistibly tugging it from her grasp, and continued talking as though to the camera. “And heck, if it were up to me, we’d use faster and shorter glass for just about everything and save the long lenses for helicopter rides.”

Karli smelled Jake’s skin as he pried the camera from her. His sun-warmed scent was a mixture of fading, spicy aftershave, clean sweat, and fresh laundry. She felt the fury begin to slowly drain from her system, sticking several times on the way out to demand just how that prick could be so cavalier about calling her frigid and accusing her of having daddy issues. She was here to do great reporting, that’s all. She’d chosen television news because she had a front-row seat on life. Every day she found the extraordinary—whether she was meeting with Fortune 500 CEOs or Joe Six-Pack at the mini-mart.

And, Karli admitted to herself, she liked to be on camera. She liked to be looked at.

Because I like having the authority that goes with being on camera, she carefully thought to herself. Definitely not because of anything to do with repressed sex stuff. She searched within for a moment, and then came clean with herself: Not mainly, anyway.

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series