- Home

- H. Laurence Lareau

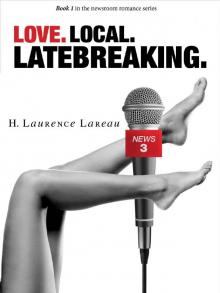

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series Page 8

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series Read online

Page 8

Karli felt the kind of rush that came when she knew an important piece of a story was beginning to come into focus. She pulled out her iPhone and texted Mary Rose to tell her she was the designated animator, then began taking notes on Vince’s research.

“The way it appears to have gone down,” Vince began, “is like this: Some engineer with antiquated ideas and training took a four-lane street that nobody had parked on for 20 years and improved it by cutting it down to two lanes and adding parking spots along the sides.

“You saw the sidewalks along there, Karli. They’re heaving with tree roots and cracks. Plus they’re slap up against the street—no patch of grass to separate them from cars. They aren’t safe even for walking, and it would be difficult to roll a bicycle or a wheelchair on them. So of course this rocket scientist of a city street engineer ignores the sidewalks while spending millions on the street. And of course the kid has to ride on that masterpiece.

“But there’s nowhere else to walk or ride. That stretch is the only east-west route available for a mile or so north and south. Ravines cut off the parallel streets. So if you want to go either way, that’s the street you’re going to use, like it or not. And if you’re a 12 year-old kid riding to where his paper route begins, you’re going to have to ride in the traffic lane of what the engineer made into a narrow two-lane street.”

“My traffic-engineer source tells me that any engineer worth his or her salt these days would have saved that kid’s life by adding bike lanes instead of parking spaces.

“The best part,” and here he waited for Karli to look up and make eye contact with him. “The very best part of this whole engineering thing, Karli, is that doing it right and saving that kid’s life wouldn’t have cost the taxpayers much of anything. Just the paint to make bike lanes and a center turn lane instead of parking spaces.”

Holly Cacciatore, the evening newscast’s greying-curls and Birkenstock-wearing producer, jumped in: “We have a freelancer in Iowa City who is interviewing one of the bicycle club’s officers there. Iowa City won some kind of award this spring or summer,” Holly checked her own notes quickly. “Yeah, here it is: Silver status from the League of American Bicyclists—in part because the city has striped a bunch of bicycle lanes on the streets. The freelancer shoots, too, so we’ll have video of those lanes so we can show the viewers what contemporary street engineering looks like.”

“Who is going to cover the texting-while-driving angle?” Jerry asked. “That’s the direct cause of this, whatever the engineers may have done. And do we have enough crews to cover all of these angles? We need to call in some people so we can give this story the team coverage it needs. And I want live shots—on the scene and in the studio—for the 10:00.”

Karli’s iPhone chirped and drew her attention away from the rest of the conversation. When she looked up, her voice had taken on a new tone of excitement. “Is there a photog I can take on an interview right away?”

“They’re all out,” Vince said, shaking his head. “Max should be back in an hour or so, though. He’s in on overtime, working on a Des Moines nightlife feature for next week.”

Damn that Jake, Karli thought yet again. I need him for this story, but he can’t be bothered to come in and do his effing job. After Karli found out that the weekend skeleton crew was stretched as far as it could go and that the reserves who had been called in wouldn’t be arriving in time for what she needed, she found some available equipment and schlepped it all out to her own car.

She didn’t want to take a marked news car to this interview. And it was probably best that she would be alone while doing and shooting the interview. She had done the shooting and interviewing all by herself for years in Palm Beach, so she knew how. She was surprised at how tentative she felt with the camera gear now, after having Jake shoot her stories for only three months or so. The camera had always just been a machine to her, but she had seen in the last few months how Jake transformed it into a storytelling tool, capturing images that she couldn’t have conceived—and if she had been able to envision them, she was coming to understand that Jake had an artist’s passion for creating visuals that she lacked the patience to develop.

As she drove to the interview, Karli reflected on how terribly sad the story was. The day had already been packed with emotional extremes and more were on the way. So she had a hard time sorting through her feelings. She was thrilled with the texting scoop, nervous and relieved about not doing the doorstep interview with the family, excited and apprehensive about the interview ahead, and there were still other subliminal feelings that were just beyond her ability to see or name them.

Both she and Jake had refused to go to the family’s doorstep with camera rolling. Karli knew why she’d refused, but she was confused about Jake’s reasons. I suppose it makes sense that he would refuse the ambush interview if he knows the kid.

And it had been obvious that he’d known the boy and that news of his death had devastated him. He responded like it was his brother or son who’d died, she thought. Jake obviously loved this Anderson boy—like he loved that Brian kid at the fair. He was really very sweet at the fair, teaching that boy how to be a man with the handshake thing and all. He must’ve been teaching this boy, too.

How does a news photog become so connected to these kids? she wondered. He cares about them enough that he actually refused to cover the story by trying the ambush-interview at the family’s door, she thought. And that’s not like a guy who has been a news photog for as long as Jake has.

Images of Jake flashed through Karli’s mind: The rock-hard physique bent earnestly around his camera, all of his energy trained, laser-like, on the viewfinder; his lean form stretching up to adjust the light atop a fully extended stand; his furious face asking her how she covered news in the tropics; and his firm handshake with young Brian at the State Fair. He had layers, this guy. He wasn’t just some shooter: he loved kids; he told her she was pretty; he gave her a pork chop like it was a diamond necklace; he shared his State Fair and the movie about it with her like they were treasures. Karli reflected that Jake was probably a good role model for the boys in his life. Then Karli remembered the building crescendo she’d felt right between her hip bones when he had complimented her, and she flushed with renewed excitement. Who, she wondered, are you, Jake Gibson?

Three NewsFirst Newsroom

The 10 O’Clock newscast

Saturday, October 5

Karli surprised all of the newsroom brass—and, later, especially the competition—when she asked the producer for a minute and a half to open the Saturday evening show. She had gone to her interview alone and had edited it with the help of a sworn-to-secrecy Mary Rose.

In the control room, Chuck the director had the technical director set up to run audio and video from the network feed and asked the engineer in master control to hand the station over during the last network commercial break. “Ready video 1 for the open,” he called during the last commercial, his finger poised over a timer. As the last commercial faded to black, Chuck snapped his timer and called, “Roll video 1, speed, and take it.” The technical director swung a fader lever to put the video on the air, and the sound engineer punched up the corresponding source. Energetic music mixed under the announcer’s voice as logos and portrait-shots of the anchors swung dizzily through the frame: “With Sophia Refai and Stu Heintz, this is Three NewsFirst at Ten...” As the frantic music played through the monitor speakers, headsets, and earpieces that kept all the various crew members in sync, Chuck called out, “Ready camera 1 and open mic on Stu, in 5, 4...” On the studio floor, Stu Heintz, the new weekend male anchor, watched as the floor director counted out loud and flashed fingers to show, “...3, 2...” and then silently finished with a single digit that swung to point right at him as Chuck called out, “Take camera 1; ready 1 to pan for graphic.”

Stu began the show with a thin, youthful baritone attempt at solemnity, “The NewsFirst focus tonight will be on the tragic death of newsboy Darrin

Anderson.”

“And pan camera one; fade in graphic,” Chuck called. The bent bicycle appeared above Stu’s shoulder, with police tape fluttering in the foreground.

“We will have team coverage from Ames and Iowa City,” Stu continued, “on the street engineering that may have caused the boy’s death.”

“Roll video 4; and take it,” Chuck called. “Bring that traffic audio under a little,” he added to the sound man, as video of bicycles rolling alongside cars in separate lanes came up on the screen. The pre-edited video cut to a shot of thumbs flashing over a cell phone that rested against a steering wheel.

“That coverage will include analysis of Three NewsFirst’s exclusive interview with the eyewitness to the accident and the problem of distracted driving.”

“Camera 1, centered on Stu. Ready...take 1,” Chuck called. Stu’s deliberately earnest face again filled the screen.

“Plus, we will have local coverage of the community’s reaction to the tragedy and what may come next for communities throughout central Iowa.”

“Ready camera 2 with both of them,” Chuck called. “Open Karli’s mic. And take 2.” The control room monitor that showed the signal going out over the air changed to a two-shot of Karli on set with Stu.

“Three NewsFirst reporter Karli Lewis is here with the latest on the story. Karli, this is a story you’ve been covering since it broke.”

“Camera 1, you’ve got to truck over faster than that. I need that shot!” Chuck called out over the headsets as a studio camera operator wrestled the huge studio camera into position to take a head-and-shoulders shot of Karli.

“What can you tell us about reactions people are having to 12 year-old Darrin Anderson’s shocking death?”

“Stu, this is a parent’s worst nightmare,” Karli began, looking first at the anchor on set and then turning to the camera that swung toward her with her text scrolling over its teleprompter screen.

“Take 1,” Chuck snapped to the technical director, as the shot of Karli came up on the camera’s preview monitor at the last second. “Clip Stu’s mic.”

“I had an exclusive interview with Darrin’s parents this afternoon. They are traumatized and grieving their loss, and they’re terrified for other kids in their community. When I asked them what message they wanted people to take away from the terrible death of their son, they had this to say.”

In her earpiece, Karli heard Chuck cue the video from the interview. Darrin’s parents had the complexions and gin blossom noses of people who had long familiarity with alcohol, but they spoke clearly through their tears. The husband had his arm around his wife’s shoulders. They were sitting on a brown and tan plaid sofa in a nondescript living room. “We love our son,” the mother wept. “We still can’t believe it.”

The video cut to Darrin’s father saying, “Everybody thinks texting don’t matter if they are doing it. But it’s them. It was this guy. And it kills,” and at this word, Darrin’s father stuttered with barely suppressed sobs. “It kills little kids like my boy.” And Darrin’s father put his face in his hands and sobbed.

“Close those mics!” Chuck called, as the gasps of surprised response from Stu and others in the studio had been slightly audible over the air. The sound engineer, looking shamed, snapped at his board. In the newsroom, everyone exchanged stunned looks.

Karli’s story went on to tell what kind of boy Darrin had been. Mary Rose had put still photos into Ken Burns-style motion to show pictures of Darrin’s short life as Karli and people she’d interviewed told how he had taken the paper route to pay for karate and how the karate had given him confidence he’d never had before and had helped him become a straight-A student. The story ended on a photo of a bright-faced boy in a karate uniform with “Darrin Anderson, 2001-2013” superimposed over the bottom of the screen.

“Don’t forget to open their mics,” Chuck cautioned as the story came to a close. “Ready camera 2...get Sophia, too! Yes, all of them!...and take 2.”

“What a terrible loss for that family and for the community,” Stu said. “Did the family have anything else to say, Karli?”

“Take 1,” Chuck called, cutting to a head-and-shoulders shot of Karli. “2, tighten up to just Stu and Sophia. Open Sophia’s mic.”

“Stu, the family is asking to be left alone for a while. They appreciate the many people who have reached out to them, but they told me tonight that what they really need is some privacy so they can try to begin to understand and cope with their loss.”

“Take 2,” Chuck called.

“Thank you for that part of the story, Karli,” Sophia said, her face looking off-screen to where Karli sat. Then her eyes moved to the camera, and as she began speaking to the audience directly instead of to Karli, her head slowly turned directly toward the camera, an anchor’s trick to create visual intimacy with the viewer. “Our coverage of Darrin’s story continues tonight with this report on how Iowa is dealing with the texting-and-driving problem...”

The rest of the newscast demonstrated exactly why Three NewsFirst was a consistent number 1 in the ratings. The reporting delivered all the day’s teamwork—the cell phone company representative acknowledged that her company’s anti-texting campaign was a huge priority, the animation that Mary Rose and Karli had worked on together showed the truck’s fatal path as the eyewitness had described it, a legislator said Iowa needed to toughen up laws about texting, the Iowa State University engineer roundly condemned the street design and sidewalk neglect, the Iowa City bicyclists spoke eloquently about how safely engineered streets worked for all kinds of vehicles.

“Finally this evening,” Sophia Refai read in the broadcast’s closing moments, “We at Three NewsFirst have been touched by Darrin’s story and heartened by a community that wants to share its support and grief in the wake of its loss. Funeral and visitation arrangements will be on the Three NewsFirst website as soon as they are finalized. Also, a special fund has been set up to accept memorial donations; details are also on our website. Three NewsFirst will be following this story to ensure that those responsible for Darrin’s death are held accountable for making our area’s streets safer.”

It seemed like the entire Three NewsFirst team was in the newsroom late on this Saturday night, watching the broadcast. As Chuck called for all audio to be clipped and the closing shot to fade to black, the newsroom erupted in cheers. The team had pulled together and done some of the best work of their careers to cover Darrin’s story.

Jerry high-fived Karli then leaned in to ask her under the self-congratulatory hubbub, “Hey, Ace—how’d you get that kid’s parents to talk? The other stations are eating our dust tonight!”

Karli’s palms again dampened with nervous sweat. She decided to come clean rather than change course to talk about the competition. “I wrote a note with my cell phone number and invited them to call if they wanted to talk. Then I slipped it in their mail slot instead of trying to catch them as they came to the door.” Karli finished with a feeling of relief at coming clean about what she’d done, but she still feared what Jerry would say about her decision to deliberately avoid a necessary interview.

Vince had been listening in on the conversation, and he saw Jerry’s deep intake of breath in preparation for a lecture about who had the authority to make that kind of decision. “Well done,” Vince quickly rasped in order to head off Jerry’s pointless lecture. “You got an interview with the parents, and nobody else got one.” Here Karli saw Vince look pointedly at the news director, who took another deep breath, thought about it, and then nodded at Vince. Karli sighed with relief and gave Vince a quick look of gratitude.

“Vince is right,” Jerry sighed. “Good job, Karli.” His aging chair lurched as he swiveled it back to his desk.

Karli thanked them both and then looked around the people straying out of the newsroom and on toward a well deserved drink or to bed. Jake was nowhere to be seen. She went to his desk and saw that his computer was off and his coat was gone.

Where, she wondered, are you? This was supposed to be the moment when we celebrated our glory together. She reflected on the terribly downcast and quiet Jake who had come back to the station with her and left the editing to the always-competent Mary Rose. That had worked out fine because Mary Rose was doing the animation, but it was unusual for a shooter like Jake to leave important visual choices up to someone else. And it’s totally wrong for anyone to be a jerk and leave in the middle of a huge story like this. Is something wrong with him? He seemed quiet, yeah, but not like anything too terrible was up. It doesn’t seem in character for him to just duck out when the story isn’t done yet. And it doesn’t seem like him to strand me so I have to face Jerry all alone about the decision not to ambush. Something is going on with him, Karli thought. Maybe he’s sick or something. Or maybe The Dick really is a jerk.

Chapter Seven

Karate Center

Southern Des Moines metro area

Monday, October 7

Brian Johnson came out of the dojo’s locker room looking as proud as he felt in his clean white karate uniform and newly earned orange belt. Sensei Jake saw the boy’s pride and energy and tried to figure out how to keep him enthused for this special training session. “Lookin’ sharp, Brian,” he said, reaching out to pin a black ribbon on the uniform. “Now remember,” Jake said, grimacing with the effort of pushing the ribbon’s pin through the uniform’s heavy canvas, “today is silent training, and you haven’t done that before. It’s for special occasions only, and today we’re training in silence so we can all remember Darrin. So once you’re on the mat, make sure you let your breath and your uniform speak for you, okay? No words at all.”

“Sure thing, Sensei Jake.”

“Good. Make sure you look extra sharp tonight. This is an important session.”

Ever since they’d covered Darrin’s death, Jake felt as though he were always just a few seconds from shocked, useless immobility. He had worked on Darrin to get that paper route, and it had killed him. Jake realized now that he was not in any position to guide or advise people. He couldn’t even help a little boy find his way without getting him killed. At least Karli had been more like a human being than he had expected about not doing the surprise interview with the parents. He still couldn’t understand where that moment of...what was it? Kindness? Laziness? Fear?... had come from.

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series

Love. Local. Latebreaking.: Book 1 in the newsroom romance series